10. Quaternions#

We saw in Lab 5 in Transformations that we can use calculate a transformation matrix to rotate about a vector. This matrix was derived by compositing three individual rotations about the three co-ordinate \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) axes.

Fig. 10.1 The pitch, yaw and roll Euler angles.#

The angles that we use to define the rotation around each of the axes are known as Euler angles and we use the names pitch, yaw and roll for the rotation around the \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) axes respectively. To problem with using a composite of Euler angles rotations is that for certain alignments we can experience gimbal lock where two of the rotation axes are aligned leading to a loss of a degree of freedom causing the composite rotation to be “locked” into a 2D rotation.

Quaternions are a mathematical object that can be used to perform rotation operations that do not suffer from gimbal lock and require fewer floating point calculations. There is quite a lot of maths used here but in this lab sheet I’ve focussed only on the bits you need to know to apply quaternions. If you are interested in the derviations of the various equations see Appendix A - Complex Numbers and Quaternions.

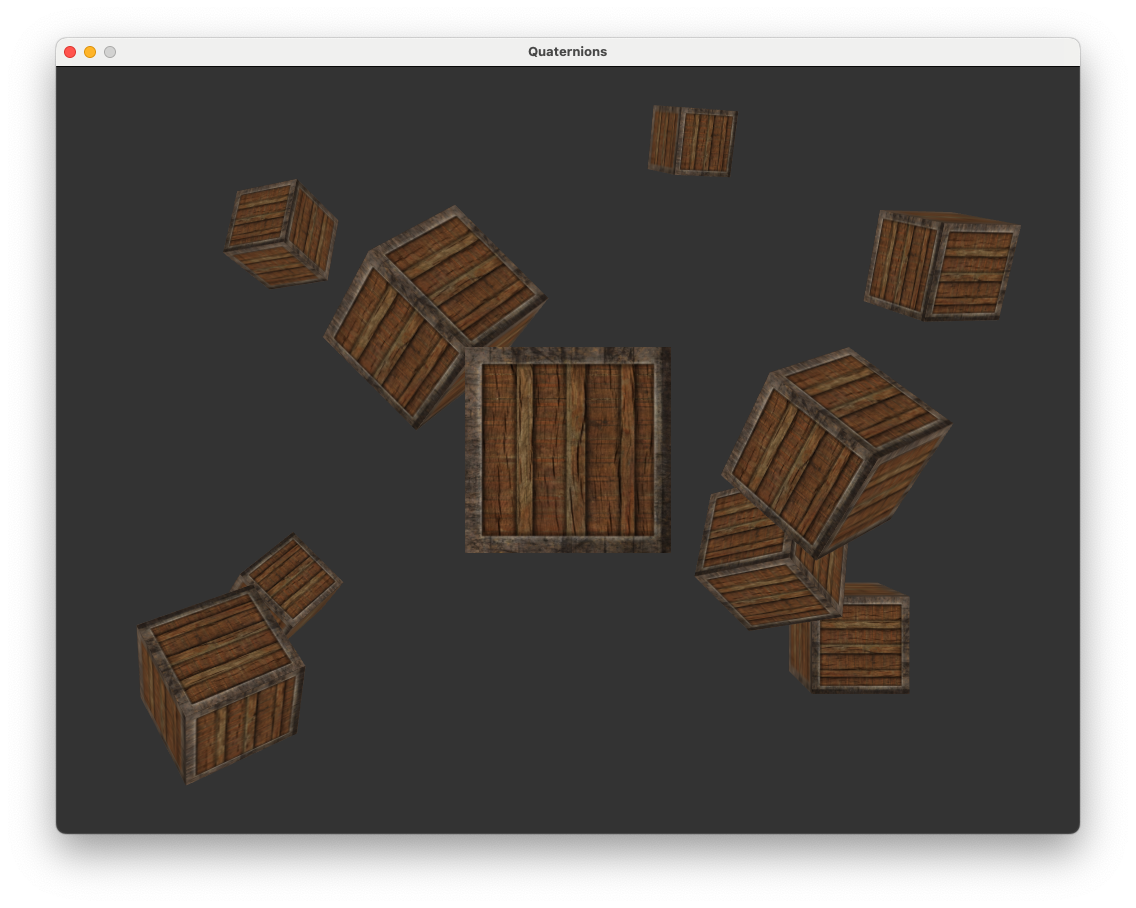

Compile and run the project and you will see that we have the scene consisting of the cubes last seen in Lab 7.

This project includes a Maths class that contains member functions that calculate the translation matrices for translation, scaling and rotation.

10.1. Complex Numbers#

Before we delve into quaternions we must first look at complex numbers. Consider the equation

Simple algebra gives the solution \(x = \sqrt{-1}\) but since a square of a number always returns a positive value, there does not exist a real number to satisfy the solution to this equation. Not being satisfied with this mathematicians invented another type of number called the imaginary number that is defined by \(i^2 = -1\) so the solution to the equation above is \(x = i\).

Imaginary numbers can be combined with real numbers to give us a complex number. Despite their name, complex numbers aren’t complicated at all, they are simply a real number added to a multiple of the imaginary number

where \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers, \(x\) is known as the real part and \(y\) is known as the imaginary part of a complex number.

Since a complex number consists of two parts we can plot them on a 2D space called the complex plane where the horizontal axis is used to represent the real part and the vertical axis is used to represent the imaginary part (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2 The complex number \(x + yi\) plotted on the complex plane.#

10.1.1. Rotation using complex numbers#

A very useful property of complex numbers, and the reason why we are interested in them, is that multiplying a number by \(i\) rotates the number by \(90^\circ\) in the complex plane. For example consider the complex number \(2 + i\), multiplying repeatedly by \(i\) gives

So after four multiplications we are back to the original complex number. Fig. 10.3 shows these complex numbers plotted on the complex plane. Note how they have been rotated by \(90^\circ\) each time.

Fig. 10.3 Rotation of the complex number \(2 + i\) by repeated multiplying by \(i\).#

So we have seen that multiplying a number by \(i\) rotates it by 90\(^\circ\), so how do we rotate a number by a different angle. Fig. 10.4 shows the rotation of the number 1 by \(\theta\) anti-clockwise in the complex plane.

Fig. 10.4 The complex number \(z\) is the real number 1 rotated \(\theta\) anti-clockwise in the complex plane.#

Recall that \(\cos(\theta) = \dfrac{\textsf{adjacent}}{\textsf{hypotenuse}}\) and \(\sin(\theta) = \dfrac{\textsf{opposite}}{\textsf{hypotenuse}}\) and since the hypotenuse is 1 then

This means we can rotate by an arbitrary angle \(\theta\) in the complex plane by multiplying by \(z\).

10.2. Quaternions#

A quaternion is an extension of a complex number where two additional imaginary numbers are used to extend from a 2D space to a 4D space. The general form of a quaternion is

where \(w\), \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) are real numbers and \(i\), \(j\) and \(k\) are imaginary numbers which are related to -1 and each other by

Quaternions are more commonly represented in scalar-vector form

We are going to add a data structure to the Maths class and some member functions to perform quaternion calculations. In the maths.hpp file add the following code above where the Math class is declared.

struct Quaternion

{

float w, x, y, z;

// Constructors

Quaternion();

Quaternion(const float w, const float x, const float y, const float z);

};

This is a data structure called Quaternion which contains the attributes w, x, y and z values and two constructor methods (one for creating a quaternion and another for creating a quaternion and initialising the \(w\), \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) values).

In the maths.cpp add the following function definitions for the constructors.

// Quaternion constructors

Quaternion::Quaternion () {}

Quaternion::Quaternion(const float w, const float x, const float y, const float z)

{

this->w = w;

this->x = x;

this->y = y;

this->z = z;

}

10.2.1. Quaternion rotations#

We saw above that we can rotate a number in the complex plane by multiplying by the complex number

We can do similar in 4D space by multiplying a quaternion by the rotation quaternion

where \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\) is a unit vector around which we are rotating (see Appendix: Quaternion rotation for the derivation of this).

Fig. 10.5 Axis-angle rotation about the vector \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\).#

We have been using \(4 \times 4\) matrices to compute the transformations to convert between model, view and screen spaces so in order to use quaternions for rotations we need to calculate a \(4 \times 4\) rotation matrix that is equivalent to multiplying by the rotation quaternion from equation (10.1).

If \(q = [w, (x, y, z)]\) is the rotation quaternion then the rotation matrix is

where \(s = \dfrac{2}{w^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2}\) (see Appendix: Rotation matrix for the derivation of this matrix).

In maths.hpp add the following method declaration to the Quaternion data structure

glm::mat4 quatToMat();

Then in maths.cpp add the following method definition

// Quaternion to rotation matrix conversion

glm::mat4 Quaternion::quatToMat()

{

float s = 2.0f / (w * w + x * x + y * y + z * z);

float xs = x * s, ys = y * s, zs = z * s;

float xx = x * xs, xy = x * ys, xz = x * zs;

float yy = y * ys, yz = y * zs, zz = z * zs;

float xw = w * xs, yw = w * ys, zw = w * zs;

glm::mat4 R = glm::mat4(1.0f);

R[0][0] = 1.0f - (yy + zz); R[0][1] = xy + zw; R[0][2] = xz - yw;

R[1][0] = xy - zw; R[1][1] = 1.0f - (xx + zz); R[1][2] = yz + xw;

R[2][0] = xz + yw; R[2][1] = yz - xw; R[2][2] = 1.0f - (xx + yy);

return R;

}

We can now calculate the rotation matrix for a rotation quaternion q using q.quatToMat(). Comparing this code to the definition of rotate() in the maths.cpp file we can see the the the quaternion rotation matrix requires 16 multiplications compared to 24 multiplications to calculate the rotation matrix based on the composite of three separate rotations about the \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) axes and a translation. Efficiency is always a bonus but the main advantage is the quaternion rotation matrix does not suffer from gimbal lock.

So it makes sense to use the quaternion rotation matrix for our axis-angle rotations. Edit the rotate() function definition so that is looks like the following.

glm::mat4 Maths::rotate(const glm::mat4 mat, const float angle, const glm::vec3 vec)

{

glm::vec3 v = Maths::normalize(vec);

float cs = cos(0.5f * angle);

float sn = sin(0.5f * angle);

Quaternion q(cs, sn * v.x, sn * v.y, sn * v.z);

return q.quatToMat() * mat;

}

Here we normalise the vector which we are rotating around before calculating the rotation quaternion q. The function then returns quaternion rotation matrix multiplied by the input matrix mat (it isn’t really necessary to do this but I wanted our rotate() function to have the same functionality as the glm version).

Compile and run your program and you should see that nothing has changed. This is good news as we are now using efficient quaternion rotation to rotate the cubes and don’t have to worry about gimbal lock.

10.2.2. Euler angles to quaternion#

Quaternions can be thought of as a orientation in 4D space. Imagine a camera in the world space that is pointing in a particular direction. The direction in which the camera is pointing can be described with reference to the \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) axes in terms of the pitch, yaw and roll Euler angles.

Given the three Euler angles pitch, yaw and roll then using the abbreviations

the quaternion that represents the camera orientation is

See Appendix: Euler angles to quaternion for the derivation of this equation. We are going to add a member function to convert from Euler angles to the rotation quaternion. Add the following to the Quaternion data structure declaration in maths.hpp

void eulerToQuat(const float pitch, const float yaw, const float roll);

and in the maths.cpp define the eulerToQuat() method

// Euler angles to quaternion

void Quaternion::eulerToQuat(const float pitch, const float yaw, const float roll)

{

float cr, cp, cy, sr, sp, sy;

cr = cos(0.5f * roll);

cp = cos(0.5f * pitch);

cy = cos(0.5f * yaw);

sr = sin(0.5f * roll);

sp = sin(0.5f * pitch);

sy = sin(0.5f * yaw);

Quaternion q;

w = cp * cr * cy - sp * sr * sy;

x = sp * cr * cy + cp * sr * sy;

y = cp * cr * sy - sp * sr * cy;

z = cp * sr * cy + sp * cr * sy;

}

We can now calculate the quaternion for the orientation given by the pitch, yaw and roll Euler angles using q.eulerToQuat().

We currently using Euler angles rotation to calculate the view matrix in the calculateMatrices() Camera class function. As such our camera may suffer from gimbal lock and it also does not allow us to move the camera through 90\(^\circ\) or 270\(^\circ\) (try looking at the cubes from directly above or below and you will notice the orientation suddenly flipping around). So it would be advantageous to use quaternion rotations to calculate the view matrix.

First we need to add an attribute to the Camera class for the quaternion that describes the direction which the camera is looking. In camera.hpp add the following code.

// Direction quaternion

Quaternion direction;

Then in the camera.cpp file, comment out the lines where we update the camera vectors and the line where we call the glm::lookAt() function and add the following code.

// Calculate direction quaternion

direction.eulerToQuat(pitch, yaw, roll);

// Calculate view matrix

view = direction.quatToMat() * Maths::translate(glm::mat4(1.0f), -position);

Here we calculate the translation matrix to move the camera to (0,0,0) and then multiply it by the quaternion rotation matrix. Of course we need the \(\tt right\), \(\tt up\) and \(\tt front\) camera vectors to move the camera, these can be easily obtained from the first three rows and columns of the view matrix. Add the following code after you have calculated the view matrix.

// Update camera vectors

right.x = view[0][0], right.y = view[1][0], right.z = view[2][0];

up.x = view[0][1], up.y = view[1][1], up.z = view[2][1];

front.x = -view[0][2], front.y = -view[1][2], front.z = -view[2][2];

Compile and run the code and you will see that you can move the camera in any orientation and we can move the camera through 90\(^\circ\) or 270\(^\circ\) without the orientation flipping around.

We are only using pitch and yaw Euler angles for our camera, lets add the ability to roll that camera as well (like a flight simulator). Where we get the keyboard input to move the camera add the following code.

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_Q))

roll -= 0.5f * deltaTime * speed;

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_E))

roll += 0.5f * deltaTime * speed;

You probably are able to work out that pressing the Q and E keys decreases or increases the roll angle respectively. Run the code and you will now be able to roll the camera!

10.3. Third person camera#

The use of quaternions allows game developers to implement third person camera view in 3D games where the camera follows the character that the player is controlling. This was first done for the Playstation game Tomb Raider released by Core Design in 1996 and has become popular with game developers with game franchises such as God of War, Horizon Zero Dawn, Assassins Creed and Red Dead Redemption to name a few all using third person camera view.

To implement a simple third person camera we are going to calculate the view matrix as usual and then move the camera back by an \(\tt offset\) vector which is a vector pointing from the actual camera position to the third person camera position Fig. 10.6.

Fig. 10.6 A third person camera.#

For our third person camera, the direction that the character is facing will be controlled by keyboard inputs where the W and S keys move the character forward and backwards and the A and D keys rotate it to the left and right. In camera.hpp add the following attributes to the Camera class.

// Third person camera

glm::vec3 offset = glm::vec3(0.0f, 0.5f, 2.0f);

std::string mode = "first";

float charYaw = 0.0f;

Quaternion charDirection;

These attributes are:

offset- the vector pointing from the character position to the third person cameramode- a string to record whether the camera is in first or third person modecharYaw- the yaw angle for the charactercharDirection- a quaternion for the direction which the character is facing

Also in camera.hpp add a declaration for the third person camera method

void thirdPersonCamera(GLFWwindow* window, const float deltaTime);

In camera.cpp add the following method definition

void Camera::thirdPersonCamera(GLFWwindow *window, const float deltaTime)

{

}

The thirdPersonCamera() method will be quite similar to the calculateMatrices() method so copy and paste the code from there into thirdPersonCamera(). We want the A and D keys to control the yaw angle for the character so edit your code so it looks like the following.

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_A))

charYaw -= 0.5f * deltaTime * speed;

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_D))

charYaw += 0.5f * deltaTime * speed;

The third person camera is moved back from the character position by translating the view matrix by the offset vector. Change the view matrix calculation to the following

view = Maths::translate(glm::mat4(1.0f), -offset) * direction.quatToMat() * Maths::translate(glm::mat4(1.0f), -position);

The last change we need to make to our third person camera method is to move the character based on the character direction quaternion and not the camera direction quaternion. Replace the code used to update the camera vectors with the following.

// Update character movement vectors

charDirection.eulerToQuat(pitch, charYaw, roll);

glm::mat4 charMat = charDirection.quatToMat();

right.x = charMat[0][0], right.y = charMat[1][0], right.z = charMat[2][0];

up.x = charMat[0][1], up.y = charMat[1][1], up.z = charMat[2][1];

front.x = -charMat[0][2], front.y = -charMat[1][2], front.z = -charMat[2][2];

We now need a way to instruct our programme whether to use the first or third person camera. In main.cpp add the following code before we calculate the view and projection matrices.

// Toggle between first and third person camera

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_1) && camera.mode == "third")

{

camera.mode = "first";

camera.yaw = camera.charYaw;

}

if (glfwGetKey(window, GLFW_KEY_2) && camera.mode == "first")

{

camera.mode = "third";

camera.charYaw = camera.yaw;

}

Here we using the 1 to select first person camera and the 2 key to select the third person camera. When switch from first person to third person camera the character yaw angle is set to the camera yaw angle so the character is facing in the correct direction. This is reversed when switching from the third to first person camera so the first person camera is facing the direction of the character.

We now instruct the program to use the appropriate method for calculating the view and projection matrices.

// Calculate view and projection matrices

if (camera.mode == "first")

camera.calculateMatrices(window, deltaTime);

if (camera.mode == "third")

camera.thirdPersonCamera(window, deltaTime);

glm::mat4 view = camera.getViewMatrix();

glm::mat4 projection = camera.getProjectionMatrix();

Of course when using the third person camera we need to render the character model. Add the following code after you have drawn all of the cubes.

// Draw suzanne model in third person camera mode

if (camera.mode == "third")

{

// Calculate model matrix

glm::mat4 translate = Maths::translate(glm::mat4(1.0f), camera.position);

glm::mat4 scale = Maths::scale(glm::mat4(1.0f), glm::vec3(0.2f, 0.2f, 0.2f));

glm::mat4 rotate = glm::transpose(camera.charDirection.quatToMat());

glm::mat4 model = translate * rotate * scale;

// Send the model matrix to the shader

glUniformMatrix4fv(glGetUniformLocation(shaderID, "model"), 1, GL_FALSE, &model[0][0]);

// Draw the model

suzanne.draw(shaderID);

}

Here we are using Suzanne the Blender mascot to act as our character model. The model matrix is calculated by translating Suzanne to the camera position (this is actually our character position as the camera has been offset) and an inverse of the charDirection matrix is used to rotate the model so it is facing in the right direction. Since the charDirection matrix is orthogonal (the columns vectors are all at right angles) this can be done using the transpose of the matrix which is much quicker than calculating an inverse of a matrix.

Compile and run the program and you should be able to switch between the camera modes using the 1 and 2 keys.

10.4. SLERP#

The another advantage that quaternions have over Euler angles is that we can interpolate between two orientations smoothly and without encountering the problem of gimble lock. Standard Linear intERPolation (LERP) is used to calculate an intermediate position on the straight line between two points.

If \(\mathbf{p}_1\) and \(\mathbf{p}_2\) are two points then an interpolated point \(\mathbf{p}_t\) is calculated using

where \(t\) is a value between 0 and 1. SLERP stands for Spherical Linear intERPpolation and is a method used to interpolate between two orientations emanating from the centre of a sphere.

Fig. 10.7 SLERP interpolation between two points on a sphere.#

Consider Fig. 10.7 where \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) are two quaternions emanating from the centre of a sphere (note that this diagram is a bit misleading as quaternions exist in 4 dimensions but since its very difficult to visualize 4D on a 2D screen this will have to do). The interpolated quaternion \(q_t\) represents another quaternion that is partway between \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) calculated using

where \(t\) is a value between 0 and 1 and \(\theta\) is the angle between the two pure quaternions \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) and is calculated using

Sometimes the to product \(q_1 \cdot q_2\) returns a negative result meaning that \(\theta\) we will be interpolating the long way round the sphere. To overcome this we negate the values of one of the quaternions, this is fine since the quaternion \(-q\) is the same orientation as \(q\).

Another consideration is when \(\theta\) is very small then \(\sin(\theta)\) in equation (10.4) can be rounded to zero causing a divide by zero error. To get around this we can use LERP between \(q_1\) and \(q_2\).

Add a method declaration to the Maths class in the maths.hpp file

static Quaternion slerp(Quaternion q1, Quaternion q2, const float);

and define the method in the maths.cpp file

// SLERP

Quaternion Maths::slerp(Quaternion q1, Quaternion q2, const float t)

{

// Check if we are going the "long" way around the sphere

float q1DotQ2 = q1.w * q2.w + q1.x * q2.x + q1.y * q2.y + q1.z * q2.z;

if (q1DotQ2 < 0)

{

// Change signs of q2 to ensure we go the short way round

q2.w *= -q2.w;

q2.x *= -q2.x;

q2.y *= -q2.y;

q2.z *= -q2.z;

q1DotQ2 = -q1DotQ2;

}

// Calculate angle between quaternions q1 and q2

float theta = acos(q1DotQ2);

// Calculate interpolated quaternion qt

Quaternion qt;

float denom = sin(theta);

if (denom > 0.001f)

{

// Use SLERP

float fact1 = sin((1.0f - t) * theta);

float fact2 = sin(t * theta);

qt.w = fact1 * q1.w + fact2 * q2.w;

qt.x = fact1 * q1.x + fact2 * q2.x;

qt.y = fact1 * q1.y + fact2 * q2.y;

qt.z = fact1 * q1.z + fact2 * q2.z;

}

else

{

// Use LERP if sin(theta) is small

qt.w = (1.0f - t) * q1.w + t * q2.w;

qt.x = (1.0f - t) * q1.x + t * q2.x;

qt.y = (1.0f - t) * q1.y + t * q2.y;

qt.z = (1.0f - t) * q1.z + t * q2.z;

}

return qt;

}

Then to apply SLERP replace the code used to calculate the direction quaternion with the following.

// Calculate direction quaternion

Quaternion newDirection;

newDirection.eulerToQuat(pitch, yaw, roll);

direction = Maths::slerp(direction, newDirection, deltaTime);

Here we use a temporary quaternion newDirection which is calculated using the pitch, yaw and roll Euler angles of the camera and then used SLERP to interpolate between direction and newDirection. Compile and run your program and you should see that the third person camera now rotates smoothly around the character.

10.5. Source code#

The source code for this lab, including the exercise solutions, can be downloaded using the links below.

main.cpp

camera.hpp

camera.cpp

maths.hpp

maths.cpp