Lab 6: 3D Worlds#

In Lab 5: Transformations we looked at the transformations can be applied to the vertex coordinates \((x, y, z, 1)\) but all of our examples were using transformations in 2D. In this lab we will take the step into the third spatial dimension and look at 3D worlds.

3D models#

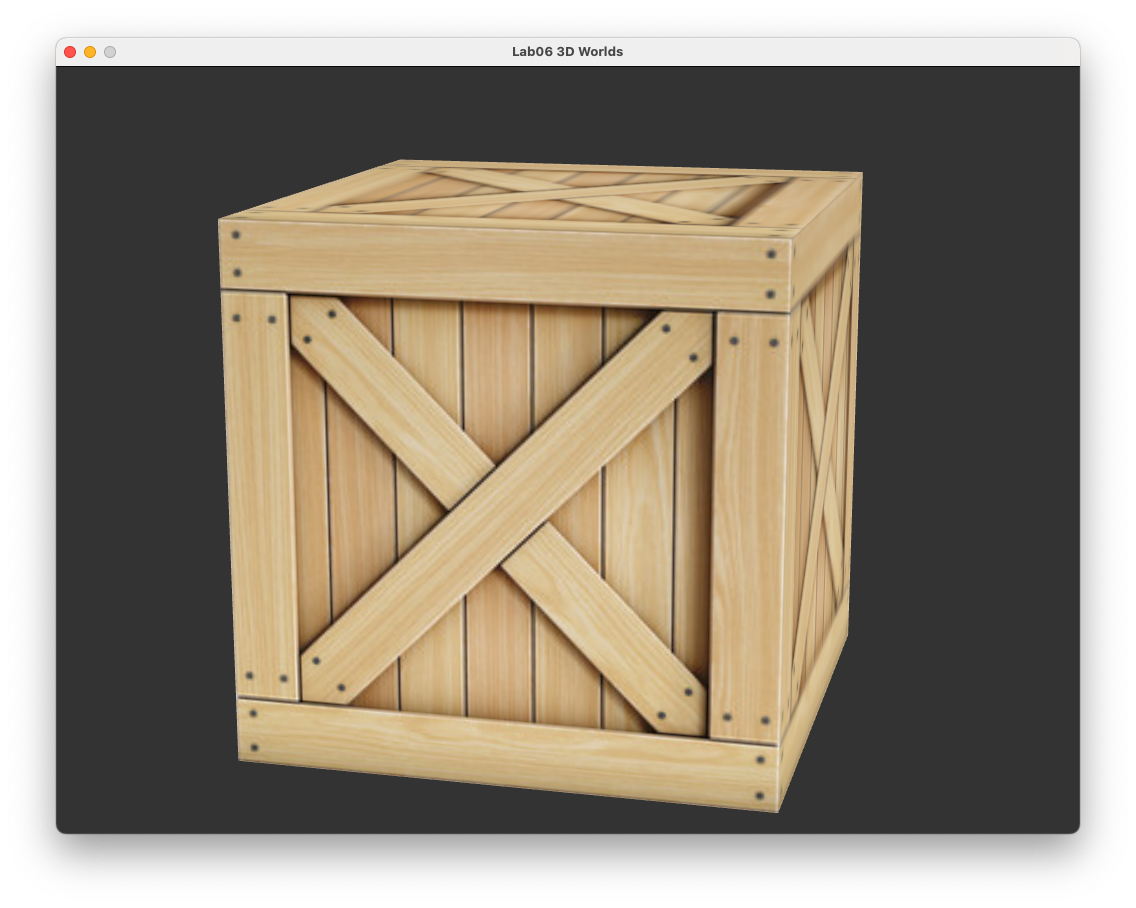

To demonstrate building a simple 3D world we are going to need a 3D object. One of the simplest 3D objects is a unit cube which is a cube centred at (0,0,0) and has side lengths of 2 parallel to the coordinate axes (Fig. 41) so the coordinates of the 8 corners of the cube are combinations of \(-1\) and \(1\). Since we use triangles as our basic cube consists of 12 triangles (6 square sides each constructed using out of 2 triangles).

Fig. 41 A unit cube centred at \((0,0,0)\) with side lengths of 2.#

Task

Download Lab 6.zip and extract the files to your computer.

Open the 3D_worlds.js file, and you will see that the vertices and indices have been defined for a unit cube.

// Define cube vertices

const vertices = new Float32Array([

// x y z R G B u v + ------ +

// front /| /|

-1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // y / | / |

1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, // | + ------ + |

1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, // +-- x | + ----|- +

-1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // / | / | /

1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, // z |/ |/

-1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, // + ------ +

// right

1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

// back

1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

-1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

-1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

// left

-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

-1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

-1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

-1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

// bottom

-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

// top

-1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,

-1, 1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

]);

// Define cube indices

const indices = new Uint16Array([

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, // front

6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, // right

12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, // back

18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, // left

24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, // bottom

30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 // top

]);

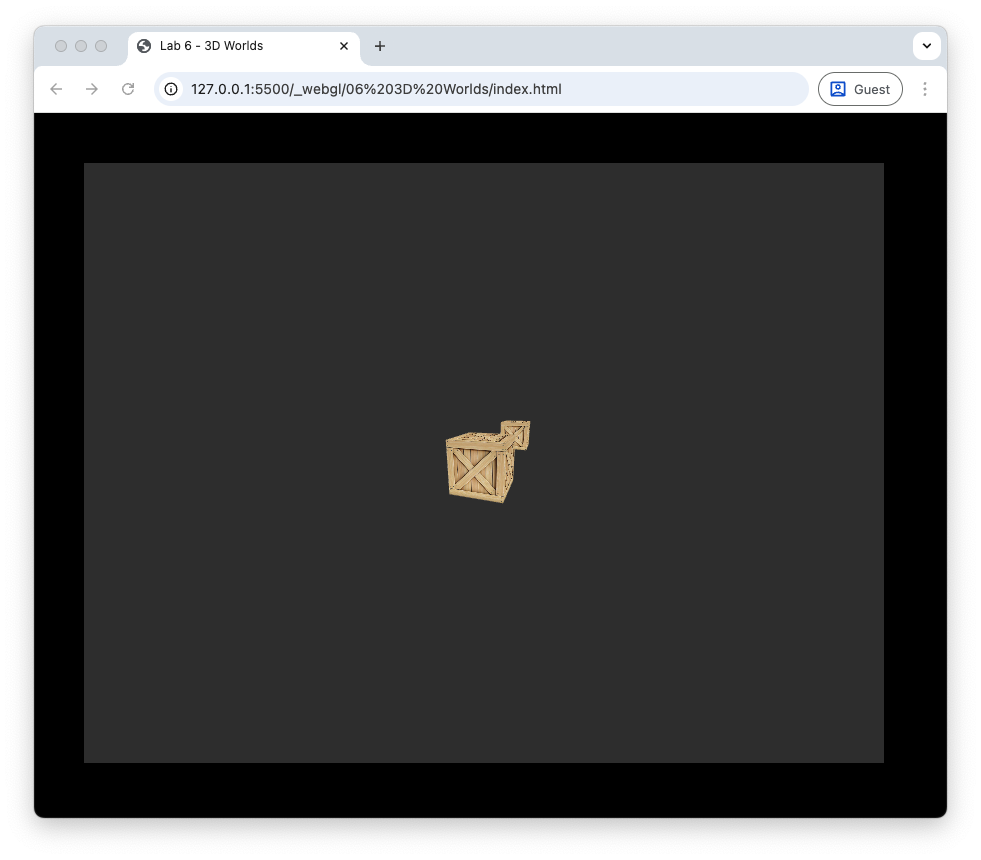

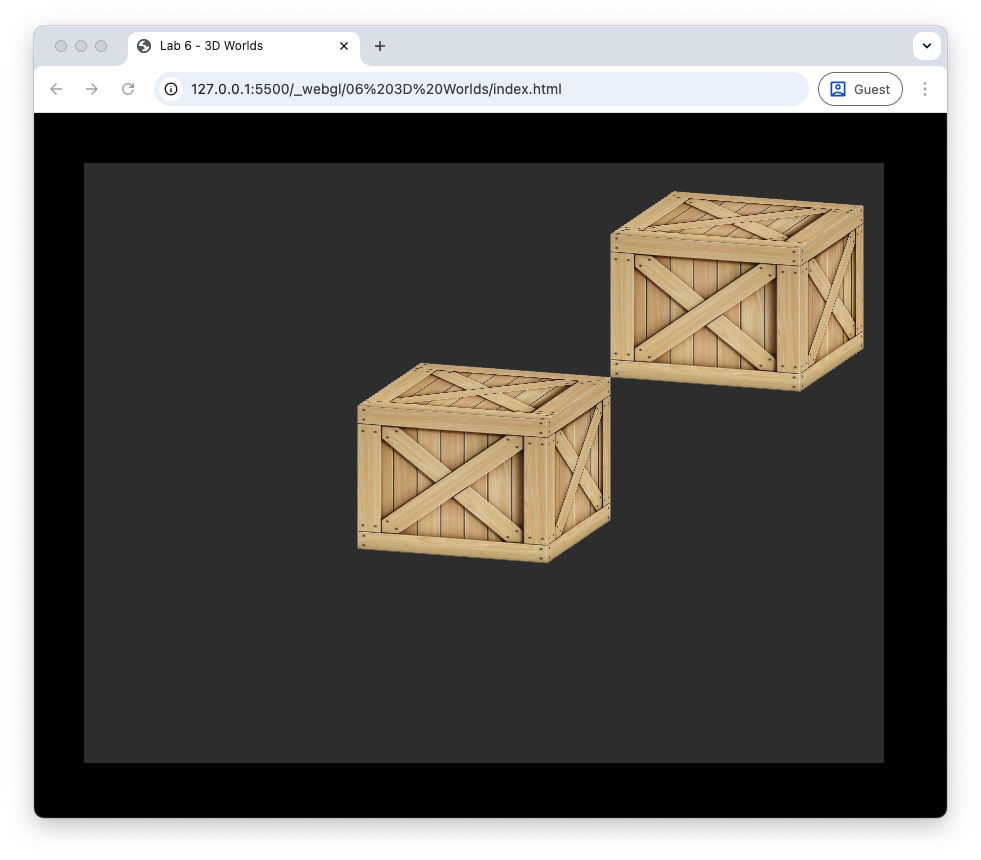

If you load the file index.html file in a live server you will see that a crate texture fills the canvas.

Fig. 42 The unit cube.#

Coordinate systems#

WebGL uses a coordinate system with the \(x\)-axis pointing horizontally to the right, the \(y\)-axis pointing vertically upwards and the \(z\)-axis pointing horizontally towards the viewer. To simplify things when it comes to displaying the 3D world, the axes are limited to a range from \(-1\) to \(1\), so any object outside this range will not be shown on the display. These are known as Normalised Device Coordinates (NDC).

Fig. 43 Normalised Device Coordinates (NDC)#

The steps used in the creation of a 3D world and eventually displaying it on screen requires that we transform through several intermediate coordinate spaces.

Model space – each individual 3D object that will appear in the 3D world is defined in its own space usually with the volume centre of the object at \((0,0,0)\) to make the transformations easier

Fig. 44 The model space.#

World space – the 3D world is constructed by transforming the individual 3D objects using translation, rotation and scaling transformations.

Fig. 45 The world space.#

View space – the world space is transformed so that it is viewed from \((0,0,0)\) looking down the \(z\)-axis.

Fig. 46 The view space.#

Screen space –the 3D view space is projected onto a 2D projection plane.

Fig. 47 The screen space.#

Model, view and projection matrices#

We saw in Lab 5: Transformations that we apply a transformation by multiplying the object coordinates by a transformation matrix. Since we are transforming between difference coordinate spaces we have 3 main transformation matrices:

Model matrix - transforms the model space coordinates for the objects to the world space

View matrix - transforms the world space coordinates to the view space coordinates

Projection matrix - transforms the view space coordinates to the screen space NDC coordinates

The Model matrix#

In Lab 5: Transformations we saw that we can combine transformations such as translation, scaling and rotation by multiplying the individual transformation matrices together. Let’s compute a model matrix for our cube where it is scaled down by a factor of 0.5 in each coordinate direction, rotated about the \(y\)-axis and translated backwards down the \(z\)-axis so that its centre is at \((0, 0, -2)\).

Task

Edit the render() function in the 3D_worlds.js file so that the calculation of the model matrix looks like the following

// Calculate the model matrix

const rotationsPerSecond = 1/3;

const angle = rotationsPerSecond * time * 2 * Math.PI * 0.001;

const model = new Mat4()

.translate([0, 0, -2])

.rotate([0, 1, 0], angle)

.scale([0.5, 0.5, 0.5]);

Here we have calculated the individual transformation matrices for translation, scaling and rotation and multiply them together to create the model matrix. The rotation angle has been calculated using the time of the current frame so that the cube will perform one full rotation every 3 seconds.

The View matrix#

To view the world space we create a virtual camera and place it in the world space. We need to translate the whole of the world space so that the camera is at \((0,0,0)\) and then rotate the world space so that the camera is pointing down the \(z\)-axis (Fig. 46). To do this we require three vectors (Fig. 48):

\(\vec{eye}\): the coordinates of the camera position,

\(\vec{target}\): the coordinates of the target point that the camera is pointing,

\(\vec{worldUp}\): a vector pointing straight up in the world space which allows us to orientate the camera, this is usually \((0, 1, 0)\)

Fig. 48 The vectors used in the transformation to the view space.#

The eye and target vectors are either determined by the user through keyboard, mouse or controller inputs or through some predetermined routine. To determine the view space transformation we first translate the camera position by negative of the eye vector so that it is at \((0, 0, 0)\) using the following translation matrix

The next step is to align the world space so that the direction vector is pointing down the \(z\)-axis. To do this we calculate three camera vectors (Fig. 48):

\(\vec{front}\) vector which extends outwards in front of the camera towards the target,

\(\vec{right}\) vector which extends outwards to the right of the camera,

\(\vec{up}\) vector which extends straight up from the camera.

These three vectors are all unit vectors (have a length of 1) and are at right-angles to each other. The front vector is calculated using

The right vector points is at right-angles to both the front and world up vectors. We can use the cross product between the two vectors to calculate this (note that the order of the vectors is important).

The up vector points is at right-angles to the front and right vectors, so this can be calculated using another cross product

Once these vectors have been calculated the transformation matrix to rotate the camera so that it is looking down the \(z\)-axis is

The translation matrix and rotation matrix are multiplied together to form the view matrix which transforms the world space coordinates to the view space.

So the transposed view matrix is

Task

Create a file called camera.js inside which enter the following code

class Camera {

constructor() {

// Camera vectors

this.eye = [0, 0, 0];

this.worldUp = [0, 1, 0];

this.front = [0, 0, -1];

this.right = [1, 0, 0];

this.up = [0, 1, 0];

}

update() {

this.right = normalize(cross(this.front, this.worldUp));

this.up = normalize(cross(this.right, this.front));

}

getViewMatrix() {

return new Mat4().set([

this.right[0], this.up[0], -this.front[0], 0,

this.right[1], this.up[1], -this.front[1], 0,

this.right[2], this.up[2], -this.front[2], 0,

-dot(this.eye, this.right),

-dot(this.eye, this.up),

dot(this.eye, this.front),

1

]);

}

}

And add the following to the index.html file before the 3D_worlds.js file is embedded

<script src="camera.js"></script>

Here we have create a Camera class that will be used to compute anything that is related to the camera. The constructor function defines 5 camera class vectors such that the camera is positioned at \(\vec{eye} = (0,0,0)\), looking in the direction of \(\vec{front} = (0, 0, -1)\) (i.e., down the \(z\)-axis). We also defined the method lookAt() which calculates returns the view matrix using equation (18).

Task

Enter the following code before the render() function in the 3D_worlds.js file.

// Create camera object

const camera = new Camera();

And add the following to the render() function before we calculate the model matrix.

// Update camera

const target = [0, 0, -2];

camera.eye = [1, 1, 1];

camera.front = normalize(subtractVector(target, camera.eye));

camera.update();

// Calculate view matrix

const view = camera.getViewMatrix();

Here we create a camera object, set the \(\vec{eye}\) and \(\vec{front}\) camera vectors so that the camera is positioned at \((1,1,1)\) and looking towards the centre of the translated cube at \((0, 0, -2)\) (using equation (15)) and then calculate the view matrix using the lookAt() method.

The Projection matrix#

The next step is to project the view space onto the screen space. The simplest type of projection is orthographic projection where the coordinates in the view space are transformed to the screen space by simple translation and scaling transformations.

The region of the view space that will form the screen space is defined by a cuboid bounded by a left, right, bottom, top, near and far clipping planes. Any objects outside the cuboid are clipped (Fig. 49).

Fig. 49 Orthographic projection.#

The transpose of the orthographic projection matrix is calculated using

where \(left\), \(right\), \(bottom\), \(top\), \(near\) and \(far\) are the coordinates of the edges of the visible space. You don’t really need to know how this matrix is derived but if you are interested click on the dropdown link below.

Derivation of the orthographic projection matrix

To derive the orthographic projection we first need to translate the coordinates so that the centre of the cuboid that represents the clipping volume to \((0,0,0)\). The centre coordinates are calculated using the average of the edge coordinates, e.g., for the \(x\) coordinate this would be \(\dfrac{right + left}{2}\), so the translation matrix is

The second step is to scale the clipping volume so that the coordinates are between \(-1\) and \(1\). This is done by dividing the distance between the edges of the screen space by the distance between the clipping planes, e.g., for the \(x\) coordinate this would be \(\dfrac{1 - (-1)}{right - left}=\dfrac{2}{right - left}\), so the scaling matrix is

Combining the translation and scaling matrices gives the orthographic projection matrix

This matrix is transposed when coding in JavaScript.

Task

Add the following method definition to the Camera class

getOrthographicMatrix(left, right, bottom, top, near, far) {

const rl = 1 / (right - left);

const tb = 1 / (top - bottom);

const fn = 1 / (far - near);

return new Mat4().set([

2 * rl, 0, 0, 0,

0, 2 * tb, 0, 0,

0, 0, -2 * fn, 0,

-(right + left) * rl,

-(top + bottom) * tb,

-(far + near) * fn,

1

]);

}

And add the following to the render() function file after we have calculated the view matrix

// Calculate projection matrix

const projection = camera.getOrthographicMatrix(-2, 2, -2, 2, 0, 100);

Here we have defined the method orthographic() that returns the orthographic projection matrix from equation (19) and used it to calculate the projection matrix.

Applying the model, view and projection matrices#

Transforming the object coordinates from the model space to the view space to the screen space is achieved using

Recall that the transformations are applied to the object coordinates in the vertex shader. We have already sent the model matrix to the shader, so we need to do the same for the view and projection matrices.

Task

Add the following code after we have calculated the view and projection matrices.

// Send view and project matrices to the shaders

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(gl.getUniformLocation(program, "uView"), false, view.m);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(gl.getUniformLocation(program, "uProjection"), false, projection.m);

We now need to update the vertex shader to use these.

#version 300 es

precision mediump float;

in vec3 aPosition;

in vec3 aColour;

in vec2 aTexCoords;

out vec3 vColour;

out vec2 vTexCoords;

uniform mat4 uModel;

uniform mat4 uView;

uniform mat4 uProjection;

void main() {

gl_Position = uProjection * uView * uModel * vec4(aPosition, 1.0);

// Output vertex colour

vColour = aColour;

// Output texture coordinates

vTexCoords = aTexCoords;

}

Task

Edit the vertex shader code at the top of the 3D_worlds.js file so that it looks like the vertex shader shown above.

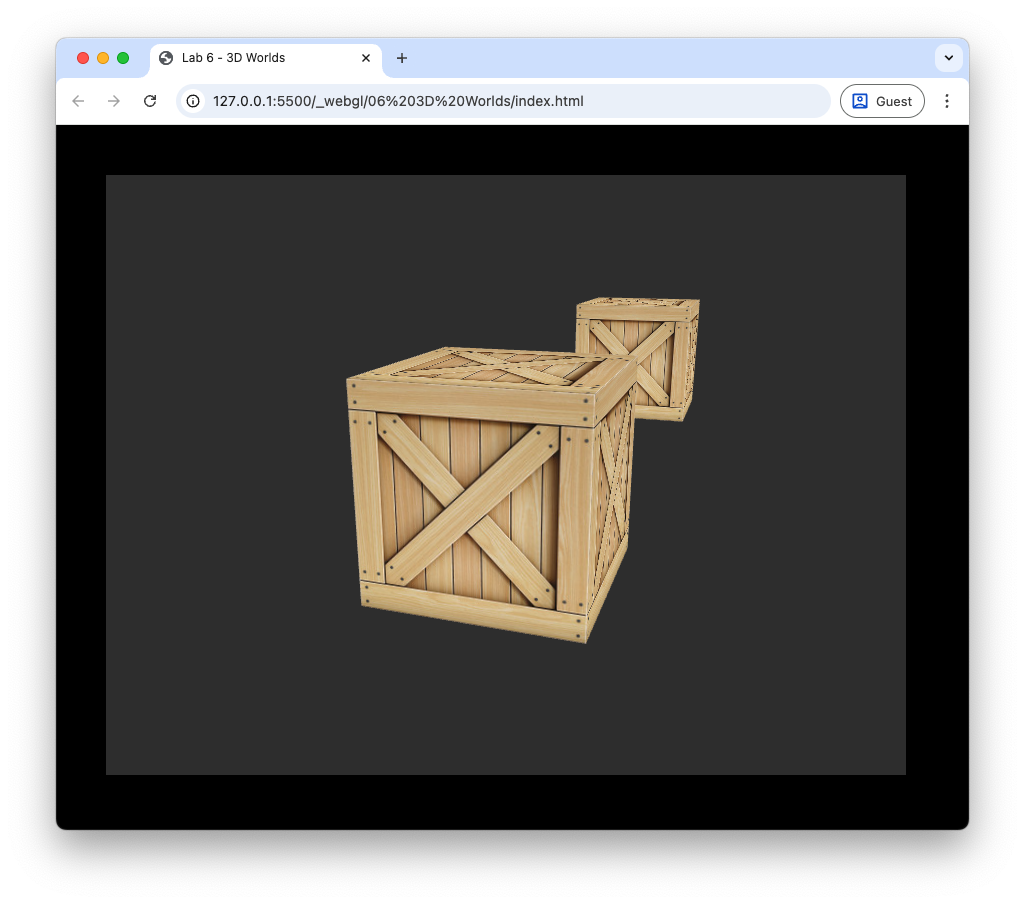

Here we have added the two uniforms for the view and projection matrices to the vertex shader and then used these, along with the model matrix to transform the object coordinates to the screen space. Refresh your web browser and you should the rotating cube below.

The depth test#

Our rendering of the cube doesn’t look quite right. What is happening here is that some parts of the sides of the cube that are further away from where we are viewing it (e.g., the bottom side) have been rendered after the sides that are closer to us (Fig. 50).

Fig. 50 Fragments further away rendered after closer fragments.#

To overcome this issue WebGL uses a depth test when computing the fragment shader. When WebGL creates a frame buffer it also creates another buffer called a z buffer (or depth buffer) where the \(z\) coordinate of each pixel in the frame buffer is stored and initialises all the values to \(-1\) (the furthest possible \(z\) coordinate in the screen space). When the fragment shader is called it checks whether the fragment has a \(z\) coordinate more than that already stored in the depth buffer and if so it updates the colour of the fragment and stores its \(z\) coordinate in the depth-buffer as the current nearest fragment (if the fragment has a \(z\) coordinate less than what is already in the depth buffer the fragment shader does nothing). This means once the fragment shader has been called for all fragments of all objects, the pixels contain colours of the objects closest to the camera.

Task

Add the following to the initWebGL() function in the webGLUtils.js file.

gl.enable(gl.DEPTH_TEST);

And change command to clear the frame buffers in the render() function to the following

// Clear frame buffers

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT | gl.DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT);

Here we first enabled WebGL’s depth test and then we clear the depth buffer at the start of the rendering of each frame. Refresh your web browser and you should get a much better result.

Perspective projection#

The problem with using orthographic projection is that is does not give us any clues to how far an object is from the viewer. We would expect that objects further away from the camera would appear smaller whereas objects closer to the camera would appear larger. To demonstrate this we are going to add another cube to our scene which is placed futher away from the camera.

Task

Add the following code after the cube indices are defined

// Define cube positions

const cubes = [

{ position : [0, 0, -2] },

{ position : [0, 0, -6] }

];

const numCubes = cubes.length;

Now edit the code used to calculate the model matrix and draw the cubes so that it looks like the following

// Draw cubes

for (let i = 0; i < numCubes; i++) {

// Calculate the model matrix

const angle = 0;

const model = new Mat4()

.translate(cubes[i].position)

.rotate([0, 1, 0], angle)

.scale([0.5, 0.5, 0.5]);

// Send model matrix to the shader

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(gl.getUniformLocation(program, "uModel"), false, model.m);

// Draw the triangles

gl.bindVertexArray(vao);

gl.drawElements(gl.TRIANGLES, indices.length, gl.UNSIGNED_SHORT, 0);

}

Here we first define an array of JavaScript objects where the position attribute are 3-element arrays containing the centre coordinates of the two cubes. We then loop through the two cubes, calculate the model matrix for each one and draw the cube. Note that have stopped the cubes from rotating by setting the rotation angle to zero. Refresh your web browser and you should see something like the following.

Fig. 51 Orthographic projection.#

The cube in the front is centred at \((0, 0, -2)\) and the cube behind is centred at \((0, 0, -6)\). Using orthographic projection both cubes appear the same size despite one being further away from the camera which is located at \((1, 1, 1)\).

Perspective projection is used to render objects where the further an object is from the camera, the small it appears in the canvas. It use the same near and far clipping planes as orthographic projection but the clipping planes on the sides are not parallel, rather they angle in such that the four planes meet at \((0,0,0)\) (Fig. 52). The clipping volume bounded by the size clipping planes is called the viewing frustum.

Fig. 52 Perspective projection.#

The shape of the viewing frustum is determined by four factors:

\(near\) – the distance from \((0,0,0)\) to the near clipping plane

\(far\) – the distance from \((0,0,0)\) to the far clipping plane

\(fov\) – the field of view angle between the bottom and top clipping planes (used to determine how much of the view space is visible)

\(aspect\) – the width-to-height aspect ratio of the window

Given these four factors we can calculate the transpose of the perspective projection matrix using

where \(top = near \times \tan\left(\dfrac{fov}{2}\right)\) and \(right = aspect \times top\). You don’t really need to know how this is derived but if you are interested click on the dropdown below.

Derivation of the perspective projection matrix

The mapping of a point in the view space with coordinates \((x, y, z)\) onto the near clipping plane to the point \((x', y', -near)\) is shown in Fig. 53.

Fig. 53 Mapping of the point at \((x,y,z)\) onto the near plane using perspective.#

The ratio of \(x\) to \(-z\) distance is the same as the ratio of \(x'\) to \(near\) distance (and similar for \(y'\)) so

So we are mapping \((x, y)\) to \(\left( -near \dfrac{x}{z}, -near \dfrac{y}{z} \right)\). As well as the perspective mapping we also need to ensure that the mapped coordinates \((x', y', z')\) are between \(-1\) and \(1\). Consider the mapping of the \(x\) coordinate

Since \(x' = -near\dfrac{x}{z}\) then

and doing similar for \(y\) we get

If we use homogeneous coordinates then this mapping can be represented by the matrix equation

where \(A\) and \(B\) are placeholder variables for now. Since we divide homogeneous coordinates by the fourth element then the projected coordinates are

So the mapping for \(x'\) and \(y'\) is correct. We need \(z'\) to be between \(-1\) and \(1\) so \(A\) and \(B\) must satisfy

At the near clipping plane \(z = -near\) and at the far clipping plane \(z = -far\) so

Subtracting the first equation from the second gives

Substituting \(A\) in the second equation gives

So the perspective projection matrix is

We now need to calculate the values of \(r\) and \(t\). The \(t\) coordinate is the opposite side of a right-angled triangle with angle \(\dfrac{fov}{2}\) and adjacent side \(n\), so it is easily calculated using trigonometry

Since \(aspect\) with the width of the window divided by the height and \(l = -r\) and \(b = -t\) then

Task

Add the following properties to the Camera class constructor

// Projection settings

this.fov = 45 * Math.PI / 180;

this.aspect = 800 / 600;

this.near = 0.1;

this.far = 1000;

And add the following method definition to the Camera class

getPerspectiveMatrix() {

const t = this.near * Math.tan(this.fov / 2);

const r = this.aspect * t;

const fn = 1 / (this.far - this.near);

return new Mat4().set([

this.near / r, 0, 0, 0,

0, this.near / t, 0, 0,

0, 0, -(this.far + this.near) * fn, -1,

0, 0, -2 * this.far * this.near * fn, 0

]);

}

Comment out the command used to calculate the projection matrix in the render() function and add the following.

const projection = camera.getPerspectiveMatrix();

Refresh your web browser and you should see something similar to the following.

Fig. 54 Perspective projection.#

Changing the fov angle#

The field of view angle determines how much of the view space we can see in the screen space where the larger the angle the more we can see. When we increase the field of view angle it appears to the user that our view is zooming out whereas a decrease has the effect of zooming in (this is used a lot in first-person shooter games to model the effect of a pair of binoculars or a sniper scope).

Experiment with the affect of changing the field of view angle.

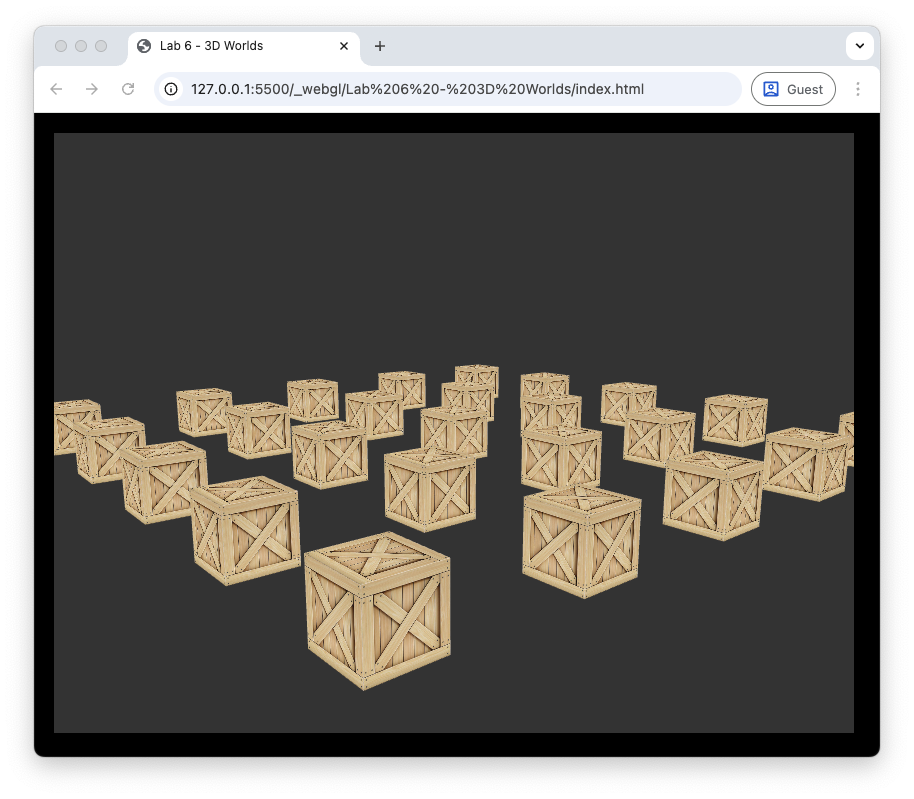

Exercises#

Create a \(5 \times 5\) grid of cubes where the centres of the cubes are 3 units apart.

Move the camera to that its position moves in a circular orbit around the centre cube at a height of 4 units off the ground. The camera should complete one full rotation every 10 seconds whilst also looking at the centre cube.

Replace every other cube with a pyramid object. To do this you will need to define the vertices and indices and create a VAO.

Rotate the cube objects about a random vector so that they complete one full rotation every 2 seconds.